The “smart stadium” market is projected to grow from $18.1 billion in 2024 to nearly $39.6 billion by 2030, according to Grand View Research—a compound annual growth rate of about 14.4 percent. Similar forecasts from other firms paint the same picture: massive spending ahead, driven by demand for IoT infrastructure, immersive fan experiences, and data-driven operations.

There’s just one problem. Much of that money will be spent by venue owners who may not have scrutinized what “smart” means.

The keyword, smart, has become a prefix attached to nearly every category of technology and infrastructure, from smartphones to smart cities. The word began to be used to describe advanced, connected phones in the mid 1990s. Its meaning has expanded since then, but it continues to function as a marketing term, something that signals innovation and modernity without requiring technical precision. In telecommunications, “5G” followed a similar trajectory as a term that came to represent both technological advancement and an alluring signal that shaped buying behavior before most customers understood what differentiated it from 4G. Today the word “smart” carries inherent cultural weight: it suggests something modern, capable, and clearly superior to whatever came before. No one wants to invest in something “dumb.”

That ambiguity creates real risk. The forecasted $39.6 billion represents money venue owners will likely spend on smart stadium tech. Whether they spend it wisely depends on whether they understand what they’re buying.

Smart is a marketing term, but it has important meaning when applied to stadium infrastructure, and that meaning has genuine operational value. A stadium becomes measurably different—more efficient, more adaptable, more capable of evolving—when its technology meets certain specific conditions.

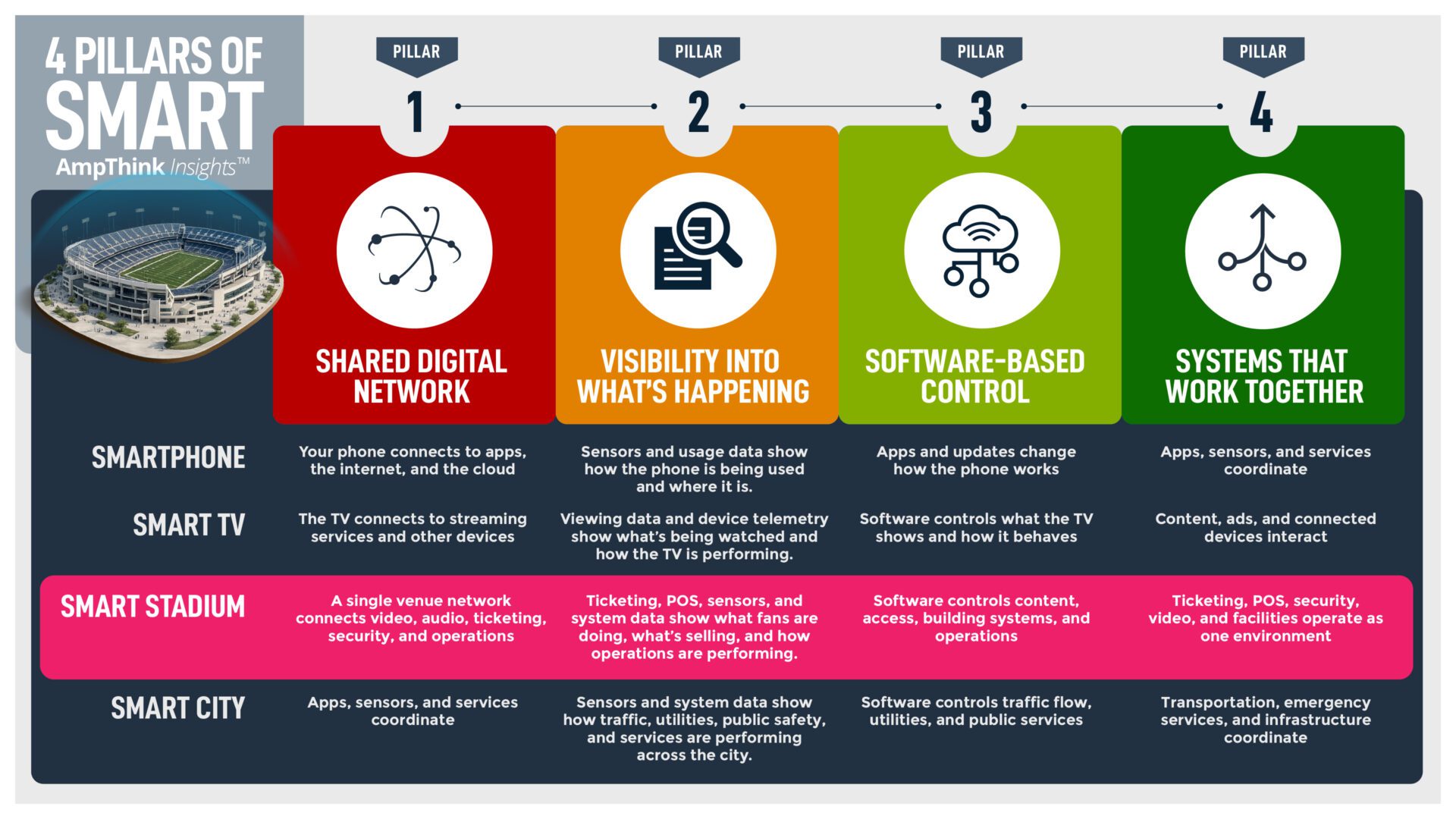

The Four Pillars of Smart Infrastructure

A stadium becomes truly smart when four conditions align. These conditions are common to all smart systems. They are pillars of smart infrastructure. Understanding what each of these pillars means—and why all four must work together—is essential for owners making smart investments in stadium tech infrastructure.

1. A Common Digital Network

For decades, stadium technology developed in discrete layers. Security cameras ran on one network. Point-of-sale terminals on another. Building controls on a third. Wi-Fi on a fourth. Each system had its own cabling, its own switches, its own infrastructure.

A converged network consolidates this physical infrastructure. Instead of parallel systems, everything runs over a single network backbone. This reduces complexity, lowers costs, and creates the foundation for systems to communicate.

But convergence alone isn’t enough. Systems can share physical infrastructure and still speak different languages. A converged network is necessary, but it’s only the first step. This is where Internet Protocol becomes essential.

2. IP Protocol as Common Language

IP provides a common format for data to move across the network and, critically, to be analyzed and acted upon. When security cameras, building sensors, broadcast and A/V systems all communicate using IP, their data can be collected, compared, and combined in ways that proprietary protocols prevent.

IP doesn’t just enable communication—it enables intelligence. A stadium might know how many people entered Gate 3, how many transactions happened at Concession Stand 7, and what the temperature is in Section 205. But if those data points live in incompatible systems, they remain isolated facts. When everything speaks IP, those facts can become insights: Gate 3 is backed up, the nearby concessions are overwhelmed, and the temperature suggests the crowd is larger than expected. Software can then coordinate a response.

3. APIs for Software-Based Management

Even when systems are networked and IP-based, they must be accessible to software control. This is where APIs—Application Programming Interfaces—become critical. An API is essentially a set of commands that allows one system to manage or query another without manual intervention or custom integration.

With APIs, a building management system can automatically adjust HVAC based on occupancy data from ticketing. Digital signage can change based on real-time crowd flow from security cameras. Concession inventory can trigger alerts based on transaction velocity from point-of-sale. These interactions happen through software, not through someone manually coordinating between different vendor platforms.

APIs transform stadium technology from something that must be physically configured to something that can be logically orchestrated. Software, not wiring, becomes the primary mechanism of change.

4. Unified Coordination (one system)

The fourth pillar is conceptual but meaningful to stadium operations: systems must be designed and deployed with coordination in mind. Even if the technology supports it, a stadium isn’t smart if each system operates in isolation, optimized for its own function without regard to the whole.

The goal isn’t just to connect systems, but to operate them as a unified platform, as one system. Staffing, energy use, content delivery, safety protocols—all align with real-world conditions rather than static plans. The building responds systematically, not as a collection of parts that happen to share network connections.

When all four pillars exist together, the venue moves from isolated gadgetry to an integrated, analytics-enabled operation. That shift promises to translate into better staffing efficiency, energy optimization, smoother fan flows, and more reliable revenue streams from concessions, merchandising, and services—ultimately affecting the bottom line. This promise is real but has yet to be fully realized.

Why All Four Rarely Exist Together

Here’s the challenge: while the technology to achieve all four pillars now exists, the traditional process of building and buying stadium technology actively works against it.

When it comes time to build or renovate, each department writes specifications for its own area of responsibility. The security team specs cameras. The IT team specs network switches. The operations team specs HVAC controls. These specifications are often created in parallel, by different consultants, with different vendors in mind.

A department head hears “smart” in vendor presentations and believes they’re making the right investment. They buy “smart” cameras, a “smart” building management system, “smart” point-of-sale terminals. On paper, they’ve made good decisions.

To be fair, these systems often deliver real value even in isolation. A smart HVAC system can generate significant energy savings without connecting to anything else. A video analytics platform can improve security operations on its own. These aren’t bad investments.

But siloed thinking leaves substantial value on the table—and often costs more than it should. A smart camera that feeds video to a proprietary security platform isn’t contributing to a smart stadium if that data can’t be accessed by other systems. A smart building controller on a closed network can’t coordinate with occupancy data from ticketing to optimize performance across the venue. When systems can’t work together, operational benefits remain fragmented and commercial opportunities go unrealized.

There’s also a financial dimension venues miss. Buying decisions are often complicated by sponsorships and technology partnerships—sometimes venues leverage purchases by offering sponsor benefits to OEMs in exchange for discounts; other times OEMs initiate deals, offering marketing dollars to get their technology deployed in high-profile stadiums. Without a unified technology strategy, venues negotiate these arrangements system by system, potentially paying more than necessary or generating less sponsor revenue than a coordinated approach would deliver.

The result: systems selected for reasons that have nothing to do with interoperability, integration, or architectural cohesion. Until all systems are designed to work together on the same network, using the same protocols, accessible through standard interfaces, and coordinated as a unified whole, the four pillars remain aspirational rather than operational.

Where AI Fits

At this point, some might assume AI can solve these integration challenges—that artificial intelligence can simply bridge disconnected systems and extract value from fragmented infrastructure. They’d be wrong, though it’s easy to see why the assumption persists. “AI” carries the same marketing power as “smart,” creating expectations that often exceed technical reality.

AI plays an important role in this story, but it arrives later than many assume.

AI doesn’t make a stadium smart. AI becomes useful once a stadium is already smart enough to feed it meaningful data. Intelligence requires visibility across systems. Historically, stadium data has been fragmented—locked inside proprietary platforms or incompatible across vendors.

As more stadiums adopt IP-based infrastructure and begin operating as unified systems, AI gains something substantial to work with. It can enhance operations, improve planning, and support decision-making—not as a novelty layer but as a natural extension of a building that already behaves like a software-defined platform.

Still, it’s worth stating plainly: a stadium remains a stadium. It is concrete, steel, fiber, power, and people. Technology doesn’t erase the realities of construction, operations, or scale. What “smart” truly promises isn’t magic but efficiency, adaptability, and the ability for technology and the built environment to evolve together instead of constantly working against each other.

A Path Forward

The four pillars provide venue owners with a clear framework for setting strategy, evaluating proposals and demanding accountability. Rather than accepting “smart” as a vague promise, owners can ask specific questions:

– Does this investment contribute to network convergence?

– Is it IP-based with standard data formats?

– Does it provide open APIs with clear documentation?

– How does it integrate with other systems to support unified coordination?

The goal is not to avoid innovation but to channel investment toward infrastructure that can continuously improve the performance of the venue. When systems converge, owners reduce duplication, simplify support, extend useful life, and gain leverage over complexity rather than remaining at its mercy. The stadium becomes something that can improve over time.

Smart stadiums aren’t about gadgets. They’re about alignment—technology designed as one system, infrastructure that’s active rather than passive, and buildings finally capable of evolving at the pace of the businesses they support.

The forecasted billions in smart stadium spending represent both risk and opportunity. For venue owners who understand what “smart” truly means and insist on the architecture to deliver it, this investment cycle could genuinely transform how their stadiums operate and perform commercially. For those who don’t, the spending happens anyway—driven by market momentum and marketing language rather than strategic clarity—resulting in fragmented systems that fall short of their potential and cost more than they should.